Memento Mori.

You are going to die.

There’s something almost impolite about saying the words aloud. They cut across the pleasant fuzz of polite conversation like a shattering dinner plate. They disrupt the rhythms of daily life, and make the modern mind wince. We’re conditioned to avoid it, dodge it, euphemize it into oblivion. Even at funerals: Welcome to the Celebration of Life of Mr. Suchandsuch. Toxic positivity around a casket. A dad-rock song. A slideshow.

You. Yes—you. You are going to die.

For the Christian, those words have a very different sound.

They don’t shout. They don’t plead. They tap you on the shoulder with the calm of a monk arranging the bones of his ancient brothers. Remember that you will die.

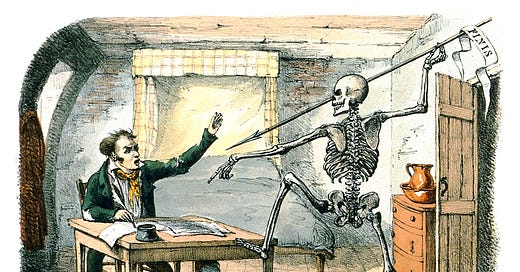

Memento Mori is a phrase that has haunted the Church for centuries—not as a threat, but as an invitation. Saints & philosophers, artists & theologians kept skulls on their desks not out of morbid fascination, but to anchor themselves in the Real. Monks in the desert carved it into stone. Priests intoned it on Ash Wednesday while smearing the cinders of palms across foreheads. This wasn’t to depress or frighten anyone. It was to help them see.

Because when we forget death, we stop seeing anything clearly.

Postmodern society, in its frantic effort to stave off age and suffering, lives in a kind of dull panic. We are constantly rushing—toward success, toward happiness, toward some imagined version of the good life that always seems just out of reach. We fill our calendars, chase our dreams, build our brands, plan our vacations... and we still feel like we’re waiting for life to begin. We imagine that we will start to really live when we retire; and then we get there, empty as space, and wonder why golf doesn’t seem to fill the hole anymore.

We fear death, so we hide it—tucking it away in hospitals and behind polished caskets and laser-engraved composite headstones. We think we’re escaping dread, but we’re actually surrendering to it.

This is why YOLO—“you only live once”—rings so hollow. It’s the desperate cry of a society terrified of missing out, terrified of boredom, a society on a dopamine binge. It is the cry of a desperate man scarfing down Doritos and wondering why he’s sick. It has nothing to do with wonder or gratitude. It’s the logic of a man sniffing cocaine off of the floor while a feast sits on the table untouched.

Memento mori is the counter-spell.

It does not say, “You are going to die, so despair.” It says, “You are going to die, so wake up.” Look around. See what is in front of you. Hear the music. Smell the bread. Hold your child. Kiss your wife. Take out the trash. Be here. This moment will never come again, and it is precious. Suck the marrow out of this moment.

To remember death is to live the kind of life that knows its value.

But there’s more than just being shocked into the mental posture to live in the present. There’s also a promise. Because death, as we know it, is not what it once was.

Scripture tells us that “the wages of sin is death.” And it’s true. We die because we are fallen. We turned away from God, the source of life, and what else could follow but decay? That’s the curse. But in Christ, something radical has happened: the curse has been inverted. Death has become the doorway to life.

By dying, Christ trampled death. By passing through it, He made it passable. And now, the very thing that once ended us has been made to begin us. His death opens the gates to eternal life, and suddenly the whole world has been turned inside out.

Now, we die INTO something. And every death—not just our final one, but every little death: of pride, of ego, of sin—is a seed.

When you meditate properly on death, you begin to see a pattern: All things that live, live off the dead. Plants grow in the matter of rotted leaves. Our food is grain ground down, flesh that once breathed, fruit fallen and consumed. Even our bodies—bones and blood and thought—are built from minerals and primeval water, atoms passed through countless other lives, other bodies, other deaths.

This is the shape of creation. It is not comforting. It is not clean. But it is beautiful. It is metaphysically and physically thrifty. Death feeds life. And in Christ, death has been hallowed.

This is the first note of Viriditas—the greening power of God—that we will speak of more later. But even here, at the edge of the grave, we see flowers budding.

Remembering your death does not cause despair. It calls you back to the feast. It reminds you that life is not a grind or a gamble. It’s not a ladder or a performance. It is a gift, given moment by moment, and none of it can be held. Only received.

Don’t run. Don’t numb yourself. Don’t wait for the perfect time—don’t wait to live. Don't assume there's more life coming around the corner.

Instead: make the call. Write the letter. Walk the dog. Light the candle. Go to confession. Start the thing. End the thing. Forgive. Rest. Stretch. Give thanks. Plant something. Laugh at the joke. Eat the steak. Let the juice run down your chin.

And pray. And fast. And sing.

You are dust. But dust that breathes. Dust that sings.

Because when you stop assuming that you will live forever, you start learning how to live well.

This is the weird and unexpected gift of Memento Mori: it is not the end of joy—it’s the beginning of it.

.

+Pax+