A Declaration of Dependence

On What We Owe the Empire; Or, How to Think about America in a Way that Doesn't Cause Massive Cognitive Dissonance.

Patriotism is a virtue, defined as rendering to one’s country the honor that is due to it. It is a subvirtue of piety—giving to our parents and ancestors the gratitude owed to them—which itself is a subvirtue of justice. I am therefore obligated, in justice, to render to my country the gratitude it is owed.

But like piety, patriotism can be complicated.

I am happily blessed with excellent parents, but I know that, tragically, many are not. What does someone owe their parents, in justice, if those parents were abusive? Or if they created a home marked by moral degradation? If one’s parents were themselves impious—severing the child from their inheritance and ancestral memory—what remains owed to them in virtue?

What is the U.S.A. owed?

I want to celebrate the Fourth of July. I’m naturally patriotic. I have deep gratitude for the struggles and sacrifices of the many fine men and women who built this nation. I am moved by our stories, inspired by our soldiers. I love this land—its folk music and traditions, its food and speech. I love the big open American smile, the friendliness of the South, the bustle of the North, the ancientness of Appalachia, the wildness of the West.

But because I love these things, I despise our government. And I don’t just mean today’s problems, which everyone complains about—I mean the whole structure. The more I’ve learned about our government and its history, the more I’ve come to believe that to love America rightly, I must be opposed to her government—not just its corrupt ministers, but its very form and goals: the bloated bureaucracy, the corporate collusion, the short-sightedness, the extractive habits, the voter-pandering and voter-manipulation. It’s all part of the deal. A cursory survey of American history confirms this, again and again.

So what am I to do about Independence Day, a holiday that explicitly celebrates this system? It canonizes American democratic republicanism, treating it as inevitable and ideal. My heart is full of Boy Scout patriotism, but my studies in history, theology, philosophy, anthropology… well, they make it hard to proclaim an unambivalent American triumph. In short, my heart is torn. Torn between a virtue that I cannot neglect, and a truth that I cannot deny.

I’ve never felt fully comfortable as an American—something my parents and community know well. I’ve felt this tension my whole life. But there’s often a misunderstanding that arises when I try to express this. When folks in my rural, Southern town—my own beloved people—hear any criticism of America, they hear echoes of leftism, or of some crummy college pseudo-intellectualism. I don’t deny those things exist, and I deplore them as much as they do. Antifa riots and the 1619 project boil my blood just as much as it does theirs.

Ever since the 60’s (and perhaps before then, I haven’t done and in-depth study of this) traditional persons in the South—conservatives—are expected to be loud, public patriots. But it hasn’t always been that way; Southern patriotism has been propagandized and carpet-bagged into existence. And recently, even the proud flag-waving denizens of the Deep South have started to question. This doubt was only patched over by the enthusiasm of movements like MAGA; underneath the surface some are asking the serious question, “how proud can we really be?” PTSD veteran boys, mostly from the South, coming home from a war they didn’t understand. Government overreach and vulgar progressive ideologues. The inadequate reaction to the opioids, immigration, poverty. There is discomfort for the first time in a while, and it’s bubbling just beneath the Trump-triumph surface.

My personal discomfort with this nation doesn’t come from hatred or ideology. Like so many Americans, my questions emerge from love. I love the good things about America. But I don’t believe those goods can cover over the real and lasting damage.

So if you’re personally disturbed by my lack of patriotic fervor, please know: it stems from a long-standing conviction—shaped by my Catholic faith, my Texan and Southern identity, and my deep concern for the truth. It’s not the result of progressive education or ingratitude for sacrifice. It’s something I’ve wrestled with for a long time. And I want to speak about it carefully.

Some people have told me that if I don’t like America, I should leave it—that I’m free to go. But this is my home. I can’t leave, and I don’t want to leave. I want to grow where I’m planted—and help make this place true, good, and beautiful.

What else would a patriot do?

It’s not a simple question. And no matter how much I write and talk about it, I will never be able to cover the complexity of the issue. Many books have been written and could be written about our identity as Americans, especially Catholic Americans. The Faith has never been comfortable in this country.

I've never felt comfortable in this country. A couple nights ago, for instance, I had a dream in which I was organizing a flanking maneuver with ballistae and cavalry squadrons to liberate a neighboring castle from thugs. This is not a normal fantasy of a good American.

More concretely: I don't believe in democracy, and I don’t agree with how we interpret “equality”. I don't believe that rights can be “guaranteed” by paper governments. I don’t even think “human rights” is a good phrase—it attempts to replace older, richer concepts like natural law, human dignity, and justice. I openly reject social contract theory and believe the “general will” is a pernicious fiction. Moreover, I certainly reject the idea that individuals should be allowed to destroy and exploit and extract and "develop" their property however they like, simply because they have some money and happen to be alive. I am no individualist.

I don't even drink sodas. Despite my best efforts, I dislike football (both kinds). The older I get, the more I hate pop music, television, blue jeans, athleisure, and lawn care. See? I'm not a very good American.

But there are many things about this country that I love, and many things that are objectively good, even monumentally so. America is an extremely safe place to be for most people. It is, by nearly every count, one of the kindest and most generous nations on Earth. It is materially prosperous beyond the wildest imagination of our forbears. The world is protected (and, yes, occasionally attacked) with our military and technological might. We live with an abundance that is hard to even comprehend: thousands of options for food and drink, cheap luxuries, clothing, housing, vast amounts of low-cost entertainment, operative roads, clean water, and garbage and waste management systems of staggering complexity.

We have a lingering sense of self-determination, self-sufficiency, and moral responsibility that—while it is fading—is still very evident. We are also creative. We love making things, trying new methods, exploring new options. We work hard.

And, despite our ambivalence about Catholicism, we are a religious country in many ways. We still go to church. We still, especially in the South, believe in Jesus.

Of course, several European countries have similar benefits. They also tend to have a more relaxed and healthy lifestyles—and, it goes without saying, far more historical depth and beauty. But I would say three things to those that scoff at America from a European perspective:

First, there are far fewer meritocratic opportunities in Europe, due to ossified social structures, bloated governments, and limited educational access. While those features have some virtues, they make it far harder to, say, purchase property or rise to the level of your competence in a profession. Personal scope is limited, not always helpfully. Second, because of this, there’s a widespread lassitude—a weary cynicism about important things. It’s a coping mechanism, I think, to deal with their diminishing relevance in global affairs and their increasing servitude to idiotic ideologies that have hollowed out their cultures from within. Third, much of Europe’s material success is maintained by foreign business interests—largely American. So their critiques of our “hustle” culture often ring hollow.

Impotent. That’s the word I’d use for Europe right now. And I say that with deep sadness. It breaks my heart, truly, because Europe is filled with the treasures of Christendom—its lands, languages, and cultures are of breathtaking beauty. They have the products of Christendom without believing in Jesus. We believe in Jesus but have forgotten Christian civilization.

Europeans have long noted that America is a young country, full of vigor and impudence. That’s true enough. The fact that we are young and vigorous is obvious.

But I’m not sure I agree that America is a country.

An Identity of Anti-Identity

If we want to call ourselves a country, rather than merely a State, we must have a cultural identity. That identity cannot consist merely of abstract ideas or ideological tendencies. It cannot be defined by a shared economy or form of government. A nation is a people bound together by shared life-ways, a common language, and common worship. A country, then, is what happens when such a people inhabit and shape a particular piece of land.

This doesn’t mean that every culture is monolithic. Within a nation, there are always dissensions, minorities, exceptions. But the exception proves the rule. There is a majority to every minority. You cannot define identity by diversity. Diversity is not an identity.

National identity must have substance. It must have actual content—not just formal structures or vague ideals.

America was a nation at some point. But that bird is flown. Cue the bald eagle screech.

What did that nation look like? We see it sometimes peeking around the corner in old films or novels, or even in the words of our grandparents—maybe in some out-of-the-way little town. It had an aesthetic presence. It had codes of manners, deep beliefs. It was different depending on which place you were in: a rich tapestry of local habits and histories, but a nation nonetheless. A nation of Revolutionary ideals, Anglo-Protestant roots, and Pioneer grit. This is an oversimplification, to be sure—but not an untrue one. When you watch those old films or visit those old towns, you cannot help but notice that whatever that country was… that country is gone.

I am, to some extent, an artifact of that disappeared nation. My mother’s mother was a scion of the Adams and Wells, Lees and McCleods—families who came over with the great Puritan migrations, fired the first shot at Concord, were agitators, presidents, Confederates. My maternal grandfather was an immigrant to the United States from old Colombian and Venezuelan families, proudly Basque and Spanish, descended from Simón Bolívar and other libertadores y dictadores. He, then, was an artifact of Revolution—of the severing of our land from Europe. He was also a manifestation of that great American dream: that all may come here and have a life, have ambition. He was, purportedly, the first Hispanic man to manage a large corporation in the South. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but there’s the bootstrap dream, full of both pathos and bathos. He went from South American aristocrat to North American bourgeois. Like many immigrants, he was fiercely proud of his new country.

My father, on the other hand, comes from Frisian Catholic German stock, arriving in Central Texas before the Texas Revolution, and during and just after the Republic of Texas. His culture has no natural tie to the Revolution or its high ideals—but rather a rooted connection to land and labor. My patrilineal inheritance also contains deeply encoded American dreams: the opportunity to own your own land and live your own life in liberty and security. This was the dream of the European peasantry under the crush of bourgeois Prussian tyranny. He is the classic American Yeoman Farmer that Thomas Jefferson dreamed about, that Wendell Berry fights for. He is involved in his community, votes based on virtue, is well-informed, well-educated, responsible and good. His American dream is fading from reality. But it’s a beautiful dream.

The values manifest in my father’s side have made me fiercely in love with my land and my people. I am a native of Texas—in the sense that we grew up rural: eating from our garden, drinking from a windmill, breathing only this air, and growing tan in this sunlight. I belong to this land. But this land is empty of a history that affirms my religion, language, or habits. Its deep history is non-European, nomadic, wild. It’s beautiful, and it has absolutely shaped me—but it is not who I am.

This has caused me some very real cultural and class confusion all my life. The United States—the Americas—from which my mother’s family hails, no longer exist. And the deeper I dive into history, the more I wonder if they ever truly did.

Because whether or not we can admit it openly, America does not have a national identity anymore. The very fact that we feel the need to “forge an American identity” is evidence that it lacks one. No Bavarian has to perform his Bavarian-ness to convince himself that he is Bavarian.

My parents love this country. My community loves this country. They love it because they love the idea of freedom and self-reliance. They love it for what it has given them. There is something very noble in that, and I don’t mean to denigrate their fervor. They are proud. But of what?

Their pride isn’t in their culture, certainly. Ask them where they’re from, and someone who doesn’t speak a lick of Gaelic and has never been out of the tri-county area will tell you, with a straight face, that they’re pure Irish.

The Market of Identity

I’ve always been drawn to three things: land, folk culture, and the highest products of civilization. I love my people and the fields, the folk dances and foods—and I love great architecture, literature, music. Increasingly, though, these are the very things in shortest supply because of the prevailing success of “The American Way of Life”.

This is not an accident.

The United States of America extracts and mangles land, systematically destroys folk cultures, and scoffs at anything it perceives as elite—whether it’s walkable streets or classical music.

There are really only two powers in America: the government and the corporation. And both extract a massive tax—one on our literal inheritance (an abomination that should be abolished), and the other on our cultural inheritance.

Frankly, I’m one of the lucky ones. I at least inherited something. My heart breaks for those raised in suburbia on fast food and Cartoon Network and the internet. They have nothing but consumer nostalgia to sustain them. I at least grew up with a piece of land and a pattern of life worth being patriotic about. I grew up with a faith, and snatches of identity. Most Americans though, especially the urban and suburban, have been disinherited.

If these disinherited modern Americans are patriotic, their patriotism is almost purely propositional. It’s memetic, reactionary, rootless, almost entirely confined to aesthetics and branding. It’s historically unmoored and power-hungry, because all it’s ever known is the allure of power. U.S.A. is Number 1. That’s all they need to know. It’s their brand. And they are loyal to it. MAGA, baby.

They have no culture—just nostalgia for a country they’ve never lived in. They have no substantial cultural inheritance, no incarnate connection to the land. They worship nothing but the idea of “God bless America”. And this may be the greatest of all America’s sins: the spiritual, imaginative, and cultural crippling of its own people—and every land it touches.

The great irony, and proof, is this: even the absence of culture has been monetized into a vast Market of Identities.

I see it most clearly at the hallowed ground of the new Texan-ness: Buc-ee’s. Like anyone, I love going there—but for an anthropological trip-out, nothing beats it. There, tourists and native Texans alike buy foreign-made artifacts of their own flattened memory. Just because your frying pan is shaped like a star does not make you a cowboy. But we buy it (I do too), with relish—as if we’re standing for something, as if we’re expressing ourselves. Again, Brand Loyalty.

We’re feeding into our own degradation. Paying for it. And it’s happening everywhere in America.

But this is unsustainable. Identity cannot be purchased or invented. It can only be inherited and discovered. America has made all identities available for purchase and personalization. This is not an identity. The “freedom to make of yourself what you will” is not a culture. It is anti-identity. Anti-culture. It is the end of the country—if there ever was one.

America is, and has always been, hostile to genuine cultural differences when it got in the way of profit-making. America is, and has always been, destructive of its magnificent land when it impeded business. Sometimes the American people have done differently—not because of their inherent Americanness—but because of lingering Christianity and European ethical imperatives. [For more details about this, see The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America by Eric Kaufmann, Puritan’s Empire by Charles Coulombe, Return of the Strong Gods by R.R. Reno, Wendell Berry’s prophetic masterpiece The Unsettling of America, and countless other analyses of this situation.]

The dual engines of power in the United States—the government and the corporation, the White House and Wall Street, Capitol and Capital—have eventually rendered any resistance to the Industrial Nation ineffectual, by either the force of law (or in some cases force of the military), or the seduction of advertisement, propaganda, and material prosperity. It has finally swept away every rooted thing, its final triumph in the living memory of our parents, who watched the small friendly towns of America disappear in favor of highway hells. The people of America may have once had an identity, but the Power of America has never had any aim but the complete overthrow of the conditions for culture in favor of Filthy Lucre.

Some will protest: “Of course America has an identity! Remember the ’50s! Remember... whatever.”

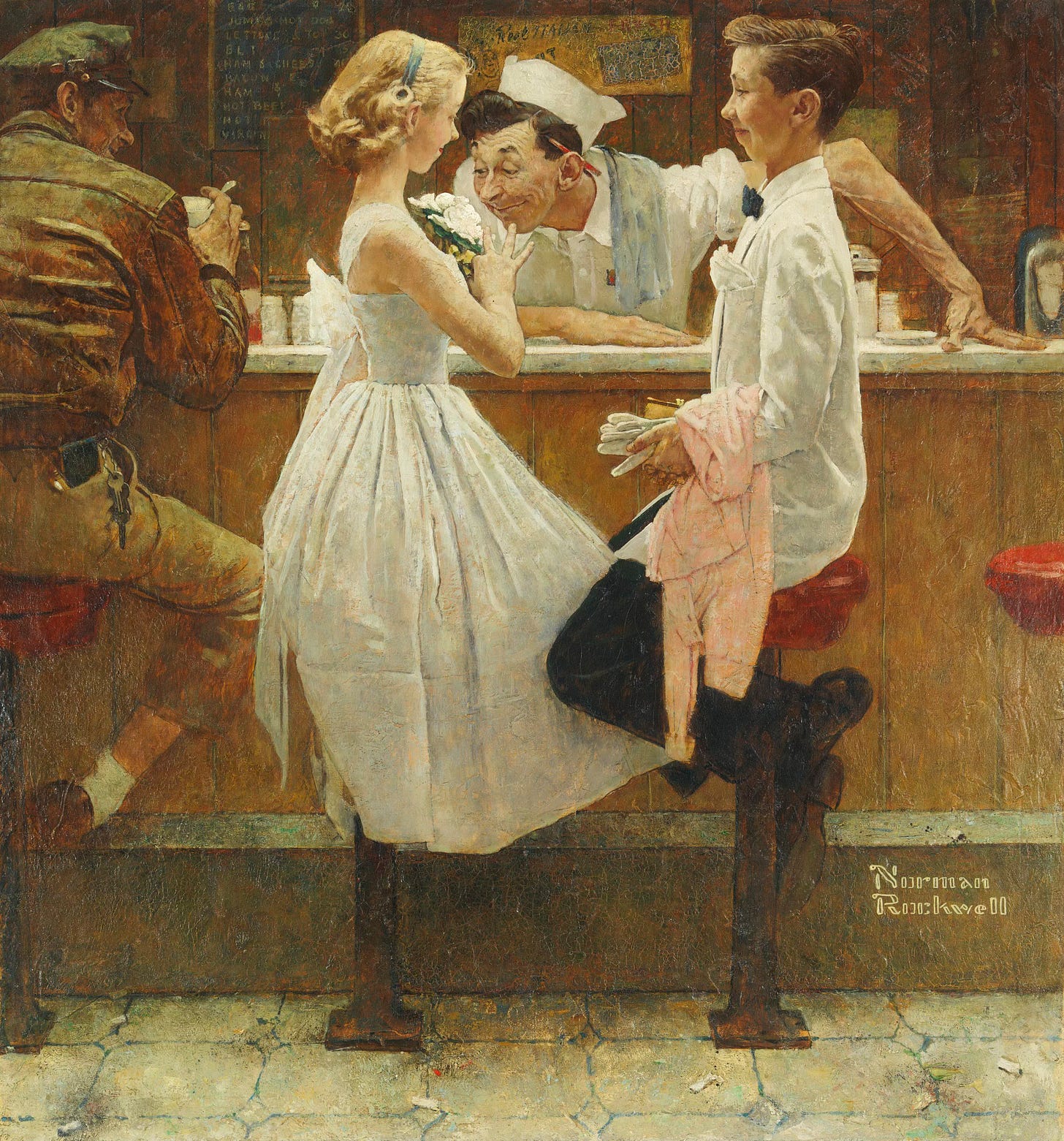

I will grant this: America once had an identity defined by a brief, fragile moment—when real culture met industrial production. That moment produced things that were good. Truly good. Our first mass-manufactured objects were beautiful. Dignified. There is something iconic and powerful in the chrome of the diner, the rumble of the early automobile, the steel icebox behind the soda counter, the striped t-shirt and baseball cap of boyhood, the Sunday dresses, the gingham, the apple pie, the weathered baseball glove. The Norman Rockwell America.

And let us not forget the last great holdout of genuinely American culture: southern Black folk before the total absorption of their identity by urban industry, big-label hip hop, sports idolatry, and drug economies. The black cowboys. The barbershops. The juke joints, the gospel churches, the soul food and oral traditions. The cadences and stories that echo down from centuries past. They, too, have suffered disintegration—marketed and sanitized for white suburban consumption, the newest form of blackface minstrel entertainment. The Indians, too, locked in their reservations, bearing the weight of complex, tragic histories—are left with casinos and tourist traps. Even the Amish have entered the Market of Identity. And while they’ve fared better than most, the cracks are beginning to show. Their decline and cultural brittleness reflect the deeper problem afflicting us all.

And the military—God help them—have had the hardest time of it. Like Roman soldiers in the late empire, they are left defending something that shifts beneath their feet. What are they defending, really? Strip malls? Stock prices? The right to form an HOA? The right to get fat on Doritos? Their valor, their discipline, their nobility exist in a vacuum, propping up a dream that no longer has a referent. My heart bleeds for the Veterans who endured suffering beyond our wildest dreams to come home to drag queen story hour. They would proudly say they are defending freedom. But freedom for what?

Movies like Red Dawn and TAPS, upholding a noble military honor… they just don’t ring true anymore. They verge on parody. Patriotism has been disconnected from place, from people, from meaning, and from faith.

The famous line—“We live here”—is barely true. People move like rootless ants, chasing salaries and escaping cost-of-living spreadsheets. The America our soldiers swore to defend is no longer purple mountain majesties and thoroughfares for freedom beat—but purple LED billboards and a highway to another chain store amalgamation.

This country has been made unlovable—despite the abundant and generous virtues of its people, despite its long lasting love of Jesus, despite its beautiful folkways and storied past. Even the new cultural quarrel—over so-called cultural appropriation—is, strangely, legitimate. And so is the bitter rejoinder. Because in the Market of Identity, everything is for sale. Every ritual. Every song. Every face, every name, every trauma. And that disorients people. It wounds people.

We are all exiles in our own native land.

And the reason we’re exiles is because our land still labors under a delusion: that you can make your own identity. We labor under the delusion that the United States of America is a country.

How can I proudly sing My Country, ’Tis of Thee, when I’m not sure what country I’, talking to? When I know that the cultural momentum of European Christian civilization has run its final lap? When the heart of our people—whatever still beats in it—has been sold to enrich some conglomerate? When the very government we celebrate on Independence Day has been complicit, every step of the way, in the slow, relentless dismantling of the culture, the people, and the land that I love?

It does not have to be this way.

The Reality of the Situation

In the midst of this anxiety-inducing society, we need a vision of clarity; not only a set of political goals, but an honest assessment of our situation. The goals have been set before us already: in the Christian vision of the City of God. The social teachings of the Church point the way forward for all of us. We must reclaim, simultaneously, our genuine faith, the health of the land, true human community, and the fruits of civilization. This is a great challenge, and will most likely take several lifetimes to fulfill. But it will never be fulfilled here if we aren’t clear what America actually is.

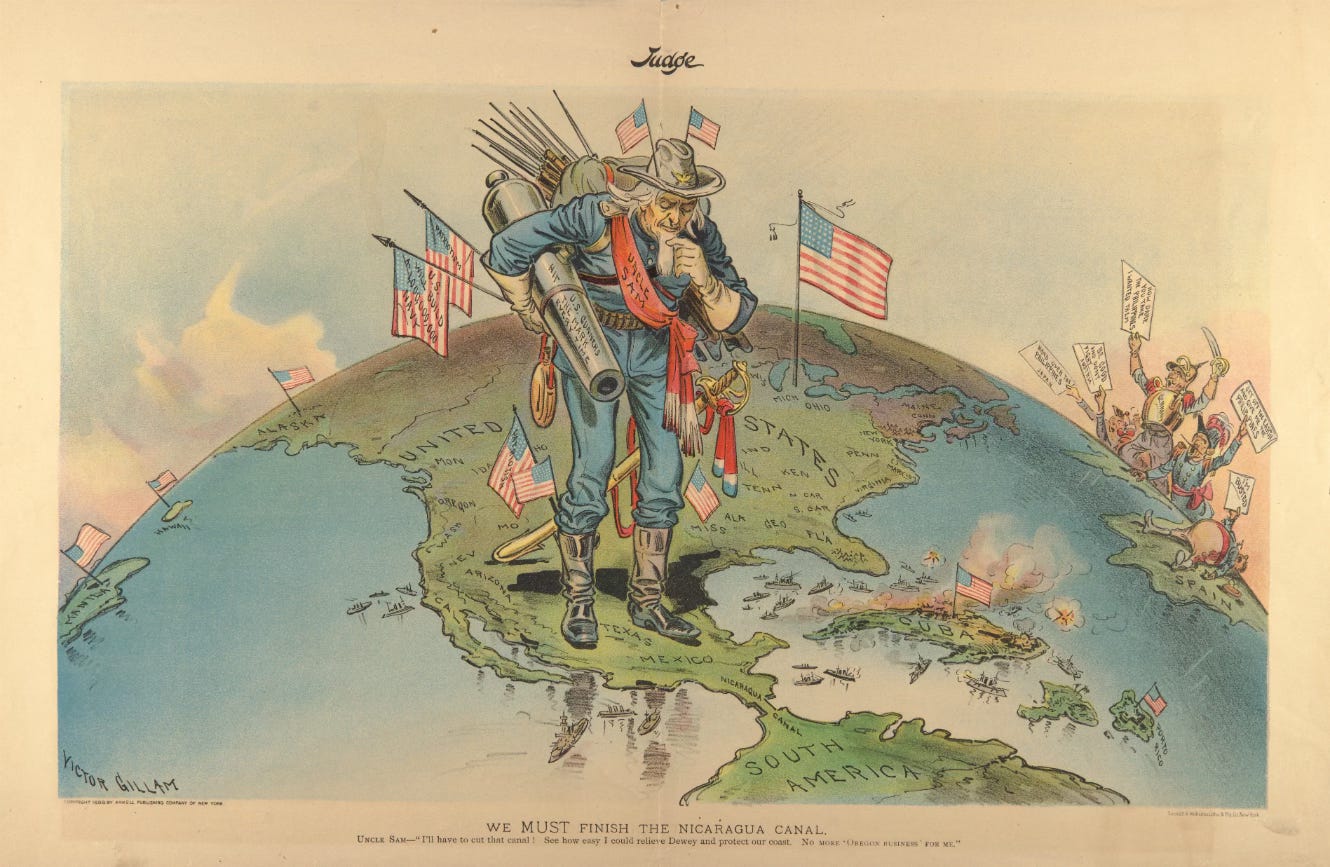

We must release some part of our broken identity and exchange it for a stronger one. Because America is not a nation, but an Empire. We must understand that we live, not in a culture, but in an Imperial order—and to be free, we must reclaim our identities from it.

With this simple re-framing of the meaning of the United States, I have been able to release some of the confusion and bitterness I’ve felt—dispelling years of tension. For a long time, I have agonized over what it meant to be American: the mixture of good and evil, nobility and shame, its deep hostility to Catholicism, the schizophrenic history and cultural incoherence. I felt like I had to either love it unreservedly or leave it—and I couldn’t do either. But when I began to think of America not as a failed country, or a confused nation, but as a functioning empire, everything fell into place. It began to make a terrible sort of sense. I began to see that The American Imperium is fundamentally separate from my cultural identity.

This is not new. It echoes the way an occupied territory of the Roman Empire must have felt. I turn to Rome because it was an Imperium honest about itself—one we understand. The United States acts like an empire but insists on calling itself a people. But the more honest we are about its true nature, the more clearly this strange and troubled nation comes into focus.

Empires, after all, are not supposed to provide you with a cultural identity; it is assumed you have inherited that already from your actual people, your native country. Empires may provide laws, roads, schools, economic prowess, and a standing army, but it does not provide a complete culture. The occupied territories are just that—occupied. To be born in these occupied territories is to receive infrastructure, but not inheritance.

But that is too simple. Let us take the example of Rome, which I think is rather apt. Rome, of course, did have a culture, and spread it. Its roots may have been mostly Greek (as America’s are mostly British), but it was still recognizably Roman.

If you were a native of Rome, of course, you would have inherited a complete Roman identity.

I do have a small claim to that “Roman” American identity—through my patrician grandmother. She is a Southern belle to the bone: soap and roses, buttermilk on ice, white gloves and Sunday dresses. She accents her vowels like Flannery O’Connor, her presence still carries something noble, though the roots are degraded. She is Anglo-Scots-Puritan-Federalist-Confederate, and from her I received the deep and sentimental Americanism of the old South—the Stars and Stripes in the breeze, a patriotic tear at the national anthem.

My mother inherited that identity strongly. Her love of America is beautiful. She believes in it sincerely, because she remembers a kind of virtuous Rome—a Cold War America that stood tall and proud.

But I never met that country. My first political memory is not Reagan or the moon landing—it’s September 11th. And as the illusions of her own era begin to wear thin—the moral failures of our statesmen, the buried weight of slavery, the wholesale abandonment of the Constitution—I can see the sadness in her eyes. She is Roman. She believes. And that belief is worth honoring. But for me, the myth was already gone.

It is a seductive dream, but I've never lived in the country she lives in. It does not inform my culture; I did not inherit it. I am not a good Roman.

It’s tragic, but it is—to some extent—inevitable. I believe that Andy Griffith America is still around here somewhere, as it is in my mother’s heart. But even if it came back, I wouldn’t quite fit there either. Because a large part of me is not Roman, but Germanic. I come from the conquered.

To be just, the conquered can still see the good in the conquerer. The American Empire has structural and social magnificence to it: maintained infrastructure, noble laws, economic security, a generalized goodwill that’s still hanging on in many places. It has a love of travel, energy, and invention. It even has many noble (if, I think, ultimately mistaken) ideals. But it cannot be a culture. Its very structure resists culture. The beauty that my parents remember—the manners, the food, the songs and stories—all came from elsewhere. They were residual: inherited European traditions or new mixtures, born of real suffering and proximity, or leftovers from that brief moment of prosperity, propaganda, and pride that characterized Cold War America. But even those now are steadily dissolved by the inevitable engines of our Empire: highways, internet, mandatory mass schooling, and economic self-segregation.

We are now an empire of scattered peoples and flattened memory.

The Fourth of July has become a last-ditch ritual of national belonging, a way to feel something collective amid the ruins.

If we can accept the reality—if we can name America for what it is—we are finally free to recover our own deeper identities. We are no longer bound to an illusion. We are no longer forced to reconcile what cannot be reconciled. America isn’t really a people; it is more like a company. A company that works to increase wealth of course, but also a company that robs us of our cultural inheritance and sells it back to us in plastic form.

We must reject this. There is no reason to believe in the sovereign right of every man to define his own identity. That is nonsense, and it leaves each generation more unmoored than the last.

With the idea of America as an Empire, I am finally free of the rip in my identity. I can both be legitimately proud as an American citizen, and a descendant of its Founding Fathers, without pretending that my culture is American. I don’t have to worship at the civic altar.

I am essentially in the same position as a Roman legionnaire from Germania or Gaul. The aqueducts run. The roads are steady and straight. There is a nobility in the struggle and privileges for its citizens. But I am also aware of a deep sorrow; that the Druids are burned and our proud Teutonic warlords slain. That my Latin is broken and my Gothic is gone. The olive oil and wine is delicious, but my tongue misses butter and mead.

So how do we remember who we are, here in the latter days of Rome, when the myth no longer holds?

How do we live in the Empire—but not OF the Empire?

Reclaiming Our True Identity

After confronting the reality of our cultural situation, what are we supposed to do? Become internet warriors? Shout our convictions into the void of comment sections? Win arguments on podcasts? No. That is not a culture. That is not a future.

This disinherited condition is not our fault—but it has become our responsibility. We did not choose to be born into a fragmented, post-cultural society, but we were born into it nonetheless. And now, whether we like it or not, the task of rebuilding has fallen to us. So how do we shoulder that burden without being crushed under its weight? I don’t pretend to have all the answers. But I’m beginning to see the outlines of what it takes.

First, we must, to whatever extent is practically possible for our families, stop participating in our own disinheritance. We have to stop feeding the very machine that grinds down our souls. That might mean leaving public institutions that cannot be reformed. It might mean changing how we educate our children, how we work, how we eat, how we spend our leisure. It might mean learning to be poor in a new and noble way. Whatever it means, we have to begin removing ourselves, piece by piece, from the habits and structures that have stolen our inheritance.

Second, we must find a place and a people that roots us—geographically, spiritually, liturgically. Find good land and good neighbors. Make a parish your home. Be where you are. Learn to live in that place, and love it. Tie yourself to its seasons, its soil, its saints. That will mean learning patience. It will mean dying to the American dream of endless reinvention. But roots are the only thing that keep a tree from falling.

Third, we have to rebuild a real culture, thread by thread. That means recovering memory. Recovering meaning. Recovering the sacramental imagination. That means re-learning the songs, the crafts, the customs, the food, the rites of passage. It means keeping feasts and fasting in rhythm with the Church’s calendar, not the market’s. It means forming children to love what is true—not what is trendy. This is slow, humble, generational work. But it is the work of civilization. And someone has to do it.

This is a lot to carry. And we will carry it with scars.

But the raw truth is that our elders, by and large, failed us. They did not pass on a living inheritance. They traded it away—for comfort, for status, for mass approval. That’s not the end of the story, but we have to name it. And now, we must do what they would not: we must go deep into our own history, into the cultural and spiritual wells that have not yet run dry, and draw from them what can be drawn. We must gather up the scattered pieces, and begin again.

Yet even more than all this—more than land, more than language, more than traditions—we must be united sacramentally. Because when we worship together, we are no longer scattered. We become one body. We receive the same Christ. We become part of the same story.

Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that we were somehow able to reconstitute the America of Norman Rockwell or Teddy Roosevelt—polished up, scrubbed clean of its more obvious failings. No doubt, things would be more pleasant, more just. The country might even be worth defending. But even then, we would not have struck at the root of the problem. Because every culture, no matter how noble, is swept away eventually. Cultures cannot save us. Nations cannot save us. The sand is always slipping through the hourglass.

And I don’t want to build my house on sand.

I want to build my house on the Rock.

Even if we made America great again, we would still have failed to make America whole. Because America has never been bound together by worship. Even in its noblest moments, America never worshipped together. It was never anchored to the heart of Christ. It was never sacramental. It was never liturgical. It was never one.

If we want a country back—not just a government, but a culture, a civilization—we must care more about our identity in Christ than any national identity. Because without Him, there is no people. Only population.

A people that does not worship together is not a nation. It is merely a crowd. And in our obsession with religious liberty—our desire to make room for every possible creed and custom—we have created a civic religion that worships nothing. A Church of America, built not around Christ but around abstract principles. Freedom. Democracy. Tolerance. These are not gods. They are tools. And they mean nothing if they do not serve Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. They mean nothing without Christ.

In throwing off the poisonous values that define American Imperial society—hyper-individualism, consumerism, rootlessness—we are not left empty. We are left ready. Ready to throw ourselves into the more ancient society of the Church. Ready to take up the culture that was always meant to be ours: the culture of Christendom.

And when you find a few other families—just a few—that see this with you and want to live it together, something powerful begins to happen. A real community takes root. Not just a social club or ideological group, but a small outpost of true civilization. The kind of place where children are taught how to work, how to pray, how to see the world sacramentally. Where their capacities are formed not to escape their origins, but to sanctify them.

From there, the long work begins. Dig into the history of your town. Learn the names on the gravestones. Read your family stories. Reclaim old devotions and folkways. Pass them on. Raise children—many of them—and place them in a village, a network, a living culture. Not just a symbolic culture of flags and barbecues, but a rooted one—with calloused hands and eyes lifted to heaven. That is what a human being needs. That is what makes a soul whole.

And so the central question of our time becomes clear. For those of us born into this American experiment, the question is this:

How do we keep the benefits of the Empire without becoming slaves to it?

How do we raise people whose feet are planted firmly on the land, and whose eyes are lifted toward heaven—in a society that is hostile to both earth and sky?

The answer, if there is one, will not be found in a movement or a party. It will be found in the Church.

A Christian Country

I said before that I am one of the lucky ones. And I meant it. I grew up in a culture—real, tangible, imperfect, but alive. I had a language, a place, a sense of belonging. I had customs and kin. I had stories. And I have threads to pick up, thanks to the goodness and vigilance of my parents. They didn’t pass everything down perfectly—no one can—but they passed down enough. Enough to begin again. I can never thank them enough.

And now, by the mercy of God, my children are lucky too. We live in a place that still remembers. The wind still carries the old songs here. My in-laws were formed by the same land, the same rhythms, the same instincts as my father. They could never imagine leaving their home, because it is not just a house—it is a sacred inheritance. And we are blessed to live near them, and near my parents, both of whom know where they come from. That is no small thing. That is the foundation of everything.

So we raise our children in this remembered place—around cattle and cucumbers, armadillos and accordions, banjos and battlegrounds. We raise them among family friends who see what’s at stake, and who are willing to make real sacrifices to preserve what can be preserved. We break bread together. We sing together. We worship together. That alone is a miracle. Blessings on blessings.

Our children will not inherit a perfect culture, but they will inherit something. Fragments, yes—but true ones. Pieces of the good life. And my wife and I are doing what we can to gather those pieces, even with our own gaps and blind spots, even with our own interrupted inheritance. And more important than all of that, they will grow up deep in the Faith. Because Christ is not just the center of all things—He is the Divine Healer. And it is through Him that our cultural healing will come. Slowly. But surely.

Yes, we are blessed beyond measure. And we know this is not the situation most people find themselves in. Many are far from home. Many never had one to begin with. Many have never seen a culture, let alone received one. But it is never too late to begin. If you can, go home—and make it a home worth defending. If you can’t go home, build one where you are. Start something small. Start a homeschool co-op. Invite your pastor to dinner. Get some Trappists to move to your town. Chair the parish picnic committee. Teach the catechism class. Learn your neighbor’s name. Plant a tree. And pray.

Neither culture nor Faith is propositional. It is not a philosophy or a checklist. It is relational, mysterious, and incarnational. It is learned in bodies and places, through suffering and joy, through rhythm and ritual and ordinary love. By occupying and living fully in the place God has given me, by staying rooted among real people—beautiful, flawed, broken people—my community helps form my children not as consumers or ideologues, but as whole persons. As souls in formation. As pilgrims who know who they are, because they know where they come from, and who they belong to.

And so here I am, in a small province of a vast and troubled Empire. But I am not afraid. If I had tied my hope to an internet movement, or a political candidate, or a collapsing economic system, I would be terrified of the future. But I haven’t. I’ve poured out my family at the feet of Christ. And in doing so, America no longer terrifies me. I can see its virtues without being seduced by them. I can name its sins without despair. I can live here without being owned by here.

Like Augustine before the fall of Rome, I can say: empires rise and empires fall. They always have. But Christ remains. His Church endures. And His kingdom is not shaken.

Ave Christus Rex.

And may God, through the hands of His faithful, remake this Empire—not into a better marketplace, not into a stronger army, but into a new Christendom.

God bless America.

This was absolutely brilliant. Thank you!!

The Nicene creed is my declaration of dependence